This article originally appeared at All Over Albany; somehow I never posted it here at Hoxsie.

The Livingston Avenue Bridge, the graceful and anachronistic swing bridge that carries trains across the Hudson River at Albany and still swings open to let larger ships reach Troy, has been part of the landscape longer than anyone now alive. It is often cited as dating to the Civil War.

Like many local legends, that’s partly almost true.

The earliest bridge across the Hudson was completed in 1804, at Waterford, by Theodore Burr, who also built the first bridge across the Mohawk at Schenectady. Despite being a wooden bridge, span at Waterford remained in service for more than 90 years.

Waterford was, as its name indicates, a good place to cross the river, but the bridge was too far from the population centers of Albany and Troy to satisfy their needs, and soon there arose a call for a bridge across the Hudson at Albany. Legislation was introduced to provide for its construction in 1814, but the booming city of Troy objected vociferously, believing that a bridge at Albany would obstruct navigation to what was still to become the Collar City.

The issue was taken up again and again over the years, and Troy found allies in the growing ferry business. As railroads grew up on both sides of the river, ferrying became big business, and the ferry operators had no desire to be put out of business by a bridge. But industry was booming in both cities, and the need to connect the shores by rail became ever more evident.

After decades of arguing, the Hudson River Bridge Company was finally incorporated in 1856 for the purpose of erecting and maintaining a railroad bridge from Albany to the opposite shore. The bridge was to be set at least 25 feet above the common tide, “so as to allow under it the free passage of canal-boats and barges without masts, with a draw of sufficient width to admit the free passage of the largest vessels navigating the river.” (The “draw” is the bridge section that moves.)

Bridge opponents did not give up once the bill was passed. A lawsuit seeking to restrain the company reached the U.S. Supreme Court. And as late as March 8, 1864, a legislative amendment proposing to reduce the width of the draw was taken up in the state Senate, the subject of a speech by long time opponent Major General Daniel E. Sickles. (Sickles served in the state Senate before going to Congress, where he shot Francis Scott Key’s son over a love triangle and invented, with his attorney Edwin Stanton, the temporary insanity defense. That’s him on the right.)

The bridge was finally built and opened on February 22, 1866. It had no particular name (and no need for one, being the only bridge). It spanned 1953 feet, with a draw 257 feet wide — and cost $750,000, a nifty 50 percent overrun from its allocation of a decade earlier. With this connection in place, all passenger trains — the Hudson River, Harlem and Boston lines — departed from the New York Central depot at the foot of Steuben Street.

Apparently the bridge caused some offense, as an act passed in 1868 directed the bridge company to build a new bridge and to demolish the previous bridge as soon as possible. If it did not do so, Albany or Troy had the right to do so and bill the company. Something must have changed by 1869, however, as another act authorizing a new bridge was passed. The Upper or North Bridge remained and was joined by another bridge at the foot of Maiden Lane in Albany, which opened December 28, 1871. Less than a year after that, in October 1872, the Union Depot opened. The “new” Union Station that stands on that spot was constructed in 1899.

Eventually the two bridges were given specific assignments: the upper bridge carried freight and foot traffic (at two cents a crossing), and the lower bridge, with its easier access to the Union Station, carried passengers.

As a side note, there were some who argued that Albany, not Troy, suffered from the construction of the bridges. In prior times, freight crossing the river had to be offloaded on one side or the other, ferried across, and loaded again onto another train. This required massive amounts of manpower, which became unnecessary once trains could cross the river. The ferries, too, suffered, but did not disappear completely for some decades. It was the 1882 opening of the Greenbush bridge (at the now-ironically-named Ferry Street), the first bridge to allow regular vehicular traffic across the Hudson, that sounded the death knell for the ferry business.

Many articles on the Upper Bridge, which eventually came to be known as the Livingston Avenue Bridge for the adjacent street that then ran all the way to the waterfront, claim that the bridge dates to the Civil War, but that the superstructure is from 1901. A letter in The Bridgemen’s Magazine in July, 1902, indicated that

the A.B. [American Bridge] Co. are making fine progress with the Livingston avenue bridge across the Hudson. The last through span has been riveted up and there remains but seven girder spans to go in on this contract, besides the draw, which will be placed in position after the close of navigation.

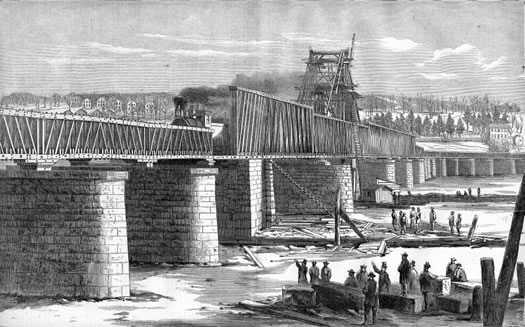

It is not clear if the limestone piers from the original bridge were maintained, or perhaps reduced in number; through filling, the river is now considerably less wide and the bridge appears to have only eight or nine piers. But the current piers look so much like those illustrated in Harper’s Weekly (above) as to raise the likelihood that the piers are original.

The last bridge to be built was the first bridge to go. The Greenbush bridge was replaced, I believe, by a later Greenbush bridge, which was replaced by the original Dunn Memorial, which was replaced by the current skyway that still goes by the name Dunn Memorial. The Maiden Lane passenger rail bridge was demolished very shortly after passenger service was removed to the Rensselaer side of the river.

And although its days may be numbered, the 145-year-old — or perhaps 110-year-old — Livingston Avenue Bridge still carries passengers across the river and swings open to let the big boats through.

There is an active and important effort to restore the pedestrian walkway that would give us a much-needed alternative for walkers, runners and cyclists to cross the Hudson without having to climb the daunting, awful Dunn Memorial. Check out the effort here.

Livingston Ave Bridge photos: Bennett V. Campbell

bridge illustration: Harper’s Weekly via Wikipedia

Sickles photo: National Photographic Art Gallery via Wikipedia

Leave a Reply