In 1850, one Ignatius Jones published the second edition of his “Random Recollections of Albany, from 1800 to 1808.” It’s interesting how many of his opinions of Albany would still find some supporters today. Jones first visited the city “just before the election of Mr. Jefferson, or the Great Apostle as he is sometimes called,” meaning 1800. (Yes, the entire book of recollections is that kind of prose.) So how did he find Albany on his first visit? He writes:

The city of Albany, in 1800, though the capital of the State, and occupying a commanding position, was, nevertheless, in point of size, commercial importance, and architectural dignity, but a third or fourth rate town. It was not, in some respects, what it might have been; but it was, in all respects, unlike what it now is.

I don’t think there’s any shortage of people who would put it as third or fourth rate now, and even more who would say it’s not what it might be.

Albany has probably undergone a greater change, not only in its physical aspect, but in the habits and character of its population, than any other city in the United States. It was, even in 1800 an old town, (with one exception, I believe, the oldest in the country,) but the face of nature in and around it had been but little disturbed . . . The rude hand of innovation, however, was then just beginning to be felt; and slight as was the touch, it was felt as an injury, or resented as an insult.

This was all nothing compared to what the rude hand of innovation would do once the Erie Canal came through and the city was transformed into one of the most important commercial centers of the young nation. But remember that even during the time Jones was writing of, there was opposition to the paving of State Street.

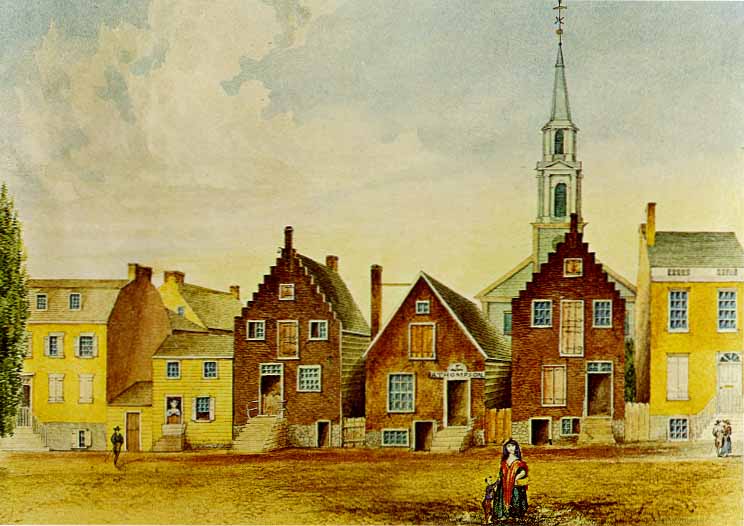

How much had Albany changed? Well, try to imagine this picture of the waterfront:

The margin of the river, with the exception of an opening at the foot of State-street, extending down to the ferry, was overhung with willows, and shaded by the wide spreading elm. The little islands below the town were feathered with foliage down to the very water’s edge, and bordered with stately trees, whose forms were mirrored in the stream below. As far as the eye could extend, up and down the river, all remained comparatively wild and beautiful, while the city itself was a curiosity; nay, a perfect jewel of antiquity, particularly to the eye of one who had been accustomed to the “white house, green door, and brass knocker,” of the towns and villages of New-England.

And one thing has definitely changed:

Nothing, indeed, could be more picturesque than the view of North Pearl-street, from the old elm at Webster’s corner, up to the new two-steepled church. Pearl-street, it must be remembered, was, in those days, the west end of town.

The church, of course, still stands, but the tree that gave Elm Tree Corner its name is long, long gone, and the picturesque quality of North Pearl Street is, in places, debatable.

Tomorrow: The City Was Dutch

Leave a Reply