We’ve already talked about a number of Albany piano makers (Marshall and Wendell, Francis P. Burns, John and Horace Meacham), and there are a number of others hardly worth mentioning. But by far the longest-established, mostly highly regarded and best remembered of all the piano makers was Boardman & Gray.

Sources all seem to agree that the first piano builder in Albany was James Archibald Gray. Born in New York City in 1815, Gray was educated at the Mechanics’ institute in New York, and around 16 with the Firth & Pond piano manufactory, No. 1 Franklin Square, New York. Some time before 1835, according to Dolge’s 1911 “Pianos and their Makers,” he was “called to Binghamton, N.Y. to superintend Pratt’s piano factory.” He was clearly a young man with a solid knowledge of piano manufacture.

William G. Boardman of Albany, originally from Wethersfield, Connecticut, knew nothing of building pianos. He was a wholesale grocer. The timelines of how he got into the piano-making game are a little screwy, even within the same writer’s narrative. The Albany Evening Times, for example, says that Boardman induced Gray to come to Albany in 1835 because Boardman found himself in possession of a piano-making company when the owner, indebted to Boardman, failed in the panic of 1838.

“Mr. Boardman was a wholesale grocer, who, in consequence of the failure of I.P. Cole, a dealer in musical instruments, in the panic of 1838, found it necessary in order to secure the money which Mr. Cole owed him, to purchase his business, which included the manufacture of pianos. Mr. Boardman was wholly inexperienced in this new venture, and disposing of his stock of groceries he was obliged to look after some skillful workman in the construction of pianos. In Mr. Gray he found such a one whose services were so acceptable that he was taken into partnership in 1837. In this manner was started the successful and celebrated piano firm of Boardman & Gray.”

So, according to the Times, Boardman brought Gray to Albany in 1835, and made him a partner in 1837, for a company he would acquire by accident in 1838 (and, generally, we talk about the Panic of 1837, but it was a long recession). Obviously, that timeline doesn’t add up. But let’s assume the particulars are about right. Other sources also put Gray in Albany in 1835 or 1836, and in partnership with Boardman in 1837.

The first factory of Boardman and Gray was on the corner of Broadway and DeWitt Street. Today, DeWitt is a stub of a stub that doesn’t even reach Broadway, but at that time it was a connector between Broadway and Montgomery that went right to the little basin of the Erie Canal, and was conveniently located (if one is making pianos) close to the lumber district. This may have been Cole’s location. Before too long the business moved to the Old Elm Tree Corner, the northwest corner of State and Pearl streets that would later be home to Tweddle Hall.

Fairly early on, James Gray was interested in constant improvements to the instrument, which was still in development. He was credited with creating an “insulated” or isolated iron frame, and a corrugated soundboard. But his most important development, and the one that seems to have been most associated with Boardman and Gray, was the “Dolce Campana” attachment. Holden’s Dollar Magazine in 1848 wrote:

“Improvement upon the Piano Forte. – Among the interesting musical topics of the month, may be mentioned the Dolce Campana Attachment to the Piano Forte. It is a new invention, patented by Messrs Boardman and Gray, of Albany, N.Y. It is quite different from any other ‘attachment’ which we have seen, and in simplicity and elegance is quite unique. As its action is not in any way connected with the strings it cannot by any possibility put the instrument out of tune. Its action is simply a pressure upon the sounding board, by which the tone is subdued and changed in quality. This tone may be compared to that of the guitar, only it is more beautiful and tender in its character. A pedal governs its action, and by a judicious management, many exquisite effects may be produced, such as repeated chords in echo, an harmonic swell, &c., &c. It is in every way superior to the harp pedal, for while its tone is soft, it is at the same time clear and melodious, and truly thrilling in its sympathetic qualities. It may be justly characterized as a new power added to the Piano Forte. We are pleased to recommend it to our readers, as something that will delight them; for we can conceive no greater delight, than to listen to a plaintive melody discoursed in the delicious tones of the Dolce Campana. We would also state that it can be applied to any instrument, with perfect safety, and at trifling cost.”

It was a Boardman and Gray with the Dolce Campana attachment that famously found favor with Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale, on her 1850-52 tour of America. The company grew and grew. Perhaps taking advantage of the Lind publicity, James Gray took several instruments to London and other cities in Europe. “His new pianos were fully tested and highly praised by distinguished professionals and other places where they exhibited,” the Albany Evening Times reported. “Among these notables were Sir Jules Benedict, George Smart, organist and composer to Her Magesty’s [sic] Chapel Royal, Charles Halle, Lindsley Sloper, Miss Kate Loder, Jane Andrews, etc.”

An ad from 1855 stated that “All their Piano-Fortes have the complete Metallic Frames, Metallic Over-Damper, Register and Cover, Improved Grand-Action, and contain every real improvement, and all are warranted to prove perfectly satisfactory.” They were then still at the Old Elm Tree Corner, 79 State and 3 and 6 N. Pearl.

Boardman and Gray was also listed in Marble Hall, 470 Broadway, in 1859, though this is likely a showroom/sales office. By then, manufacturing had moved to the corner of Broadway and North Ferry Street, in one of the largest buildings in the city, five stories high, with 180 feet fronting on North Ferry.

In 1860, that factory burned rather spectacularly, but without loss of life. “There were twenty-three rooms in the building devoted to the different departments,” The Atlas and Argus wrote. “The machine room, in which the fire originated, was about the center of the building on Ferry-street, and in it was a fire-engine of 40-horse power.” It was reported then that the company was turning out 25 pianos a week. The building and its stock were estimated to be worth $100,000, and about $50-60,000 was lost in the fire. There were about 200 finished and unfinished pianos at the time of the fire; 70 were saved, half of which were finished. The machinery was destroyed.

“Mr. Abbot, one of the foremen of the establishment, lost machinery valued at $1,400, upon which there was no insurance. He came near losing his life, too. On learning that the manufactory was on fire he hastened to the scene and rushed into the burning building for the purpose of securing his patterns. Excited and, therefore, too careless, he soon found that he was being overcome by the smoke, and barely had time enough to escape before it smothered him. Thirty-four of the workmen lost all their tools. Upon these they place an average valuation of $40, or a total of $1,360.”

This from a time when workmen were generally responsible for their own tools, and took all the risk in a situation like this. It was believed that otherwise the loss would be covered by insurance, which was spread across 19 companies. Despite the fire, they appear to have rebuilt at that site; the building later housed William McCammon’s piano factory, and it stands to this day.

In 1866, Boardman & Gray moved to a new brick building at 239 North Pearl Street, on the east side south of Lumber Street (now Livingston), and the Evening Times reported that, “Here employing a large force of skillful workmen they turned out more than a score of complete instruments monthly. The demand for their work was continually on the increase.”

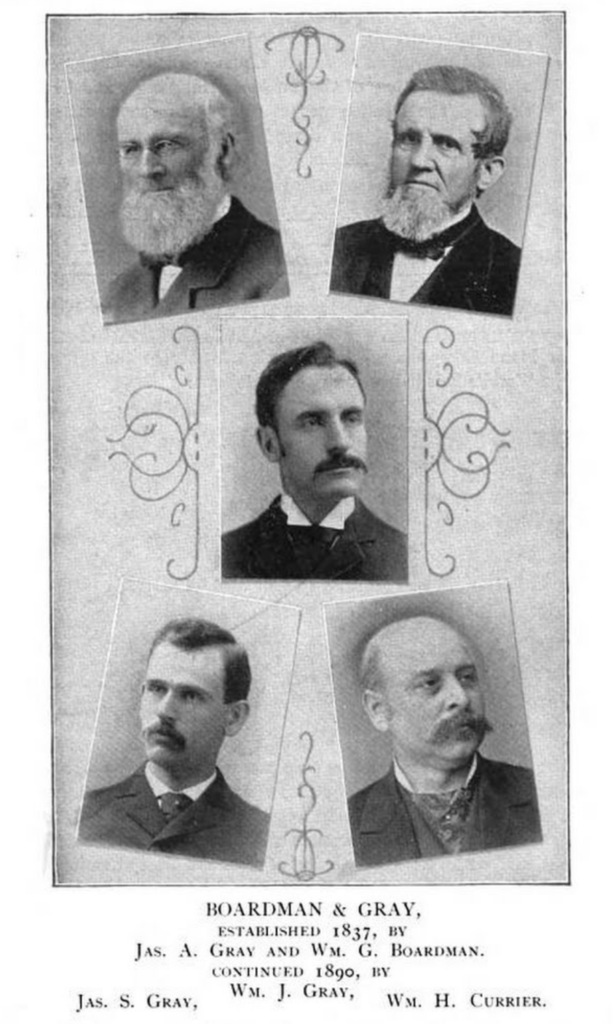

It’s widely reported that William Boardman, who lived until 1881, retired from the business fairly early, and though it’s a little hard to pinpoint exactly when, it appears to have been during the Civil War, prior to the Pearl Street move. In 1864, both Boardman and Gray are shown in the business directory at Broadway and North Ferry, though they weren’t actually listed as piano makers and didn’t have an advertisement. In 1867, Boardman isn’t mentioned as a piano maker, but James Gray is. In 1868, the company is known as James A. Gray & Co. (Wm. N. Gray), which may well mean that Boardman was completely out and that James’s son William, who would become a full partner in 1877, was instrumental in running the company. In 1873, the company was listed as James A. Gray, “manufacturers of the improved Boardman, Gray & Co. Premium Piano Forte.” Again, business continued to grow. Son James N. Gray also joined the firm; eventually, his sons, Emerson, Neil and Bradley, would join the family business as well.

They remained at the facility on North Pearl until another major fire struck in July 1885, one that was long remembered. This passage from the Albany Morning Express may be a bit grisly for some tastes:

“Nothing in years has so horrified Albany as the catastrophe of yesterday morning . . . Four gallant firemen, working faithfully at the post of duty regardless of great peril, were crushed under the fallen walls of a factory without a moment’s warning. One, Daniel Wheeler, was killed instantly. John A. Luby, mangled beyond recognition, was rescued only to die a few hours later . . . Frederick Wallen, a third victim, was taken from the ruins suffering from terrible injuries, and lingers at the hospital with no hope of recovery [and he did die the next day]. Rufus K. Townsend, a brave volunteer fireman, received painful hurts, but luckily escaped death . . . The crumbling foundation walls of Gray’s piano factory and even the site of Burch’s livery stable – now nothing but a cellar filled with debris – were tramped over by people, on whom the still heated bricks, glowing embers, and a terrible stench which rose from the burned horse-flesh had no restraining effect. In the ruins of Gray’s factory the wrecks of pianos could be seen, the iron frames blackened and twisted, while the only part of the building left standing was a towering chimney, to which ragged portions of adjoining walls adhered. The surroundings showed the terrible effects of the fire. Adjoining buildings were charred and scorched, and the shade trees on Pearl street had been stripped of foliage by the intense heat. Even the coverings of the electric light wires had been cleanly burned off for several hundred feet.”

Blaming for the deaths started early, with a fire chief being accused of having sent firefighters back into an alley after they had been warned away from it because of the potential for the wall to collapse, but that was soon disproven. There was considerable debate whether the fire had originated in the piano factory, which had been closed for two days and had no drying facilities where fire would be likely to start, or in Burch’s stable; as far as we can tell there wasn’t a conclusive determination. Following the destruction, James Gray estimated his loss at $14,000, with $10,000 covered by insurance, and he said would build again, “but not contiguous to such structures as those near the burned factory.” Marshall & Wendell “kindly offered their facilities and any aid in their power to assist the Boardman & Gray company to fulfill orders.” Within a few weeks, they had secured temporary quarters at 547 Broadway, “and expect to be able to fill all orders by October 1.”

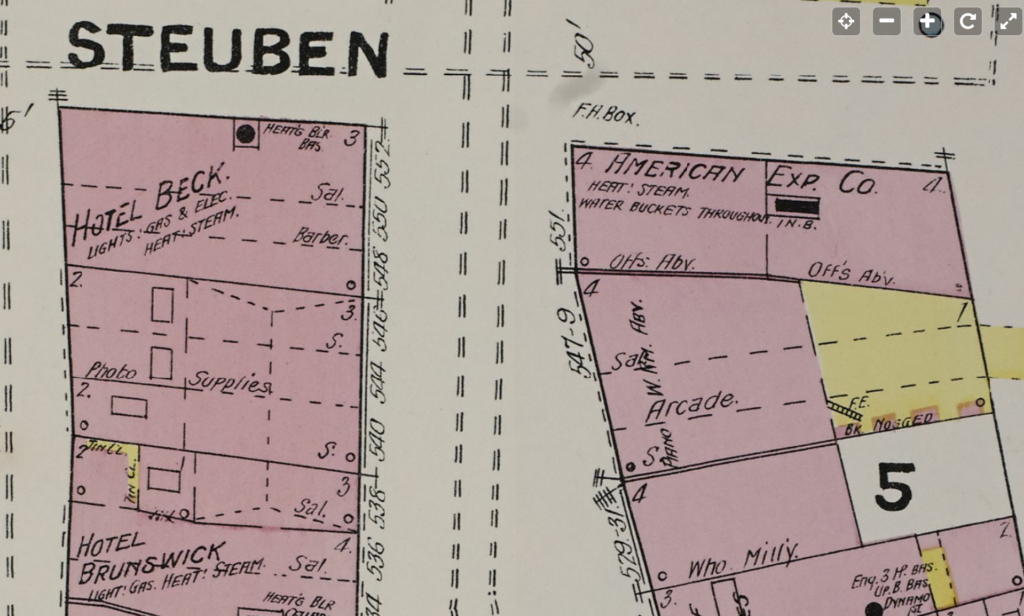

They ended up staying at 543, 545, 547 Broadway, just south of Steuben on the east side, below the American Express headquarters – not quite keeping to Gray’s thought of not being contiguous to other structures. (Today, the Dormitory Authority headquarters stands on the site.)

James A. Gray died Dec. 11, 1889, at the age of 74; his sons William and James continued the business, along with a partner, William H. Currier.

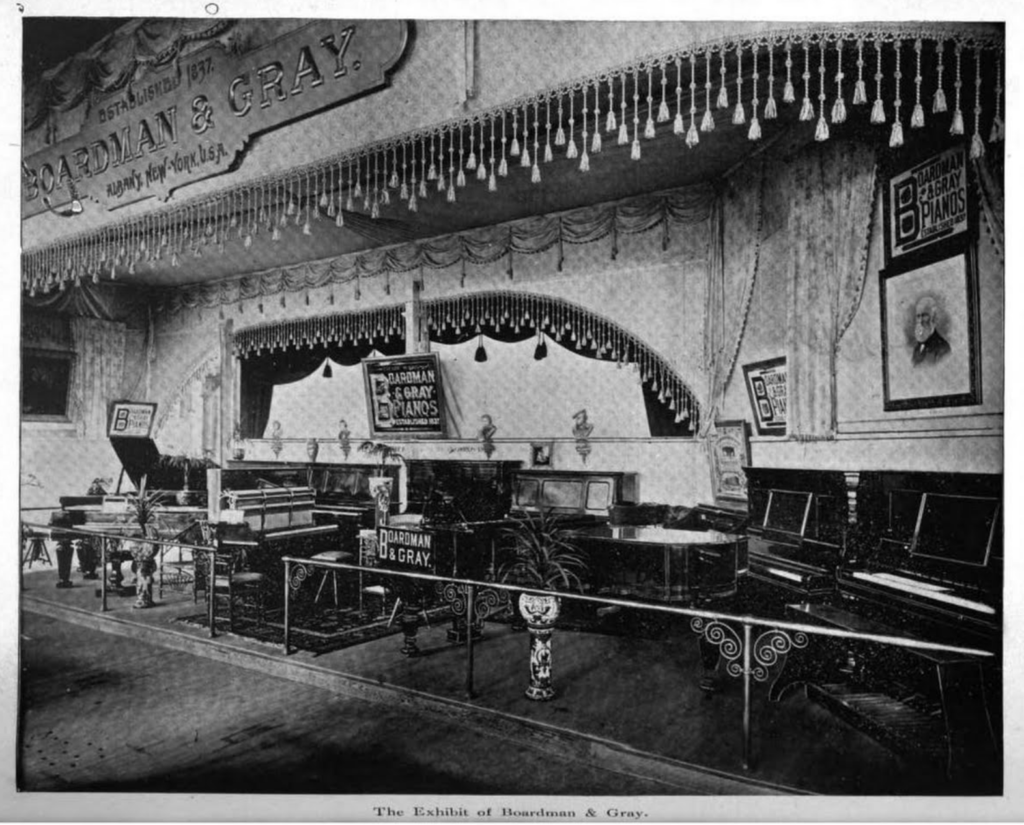

In 1893, Boardman and Gray received an award for their exhibit at the Columbian Exposition, showing eight instruments, two of which were grands. “The booth was very tastefully arranged with rich hangings and curtains, and with growing plants at intervals along the front rail.” Among the display was a square piano made in 1837, “and after fifty-six years of constant use was still in good serviceable condition possessing its original tone and not being defective in any way.”

Many years later, in 1922, they purchased a building at 7-9-11 Jay Street, at Eagle Street behind the old Albany Medical College, to serve as their manufacturing facility. It was probably around this time that they moved their headquarters to 446 Broadway, opposite the Post Office, and two doors up from the Museum Building. Whether this points to a decline in their business at that time, we cannot say, but it is clear that from the time the Great Depression began, piano manufacturing in the United States plummeted, and Boardman and Gray were not excepted. That new form of home entertainment, the radio, started to eat into piano sales; its successor, television, did even more damage. They tried to keep up with the times, selling radios and phonographic equipment. In 1927, during a two-day display of the new Ford motor cars in the lobby of the DeWitt Clinton Hotel, Boardman and Gray “installed an Automatic Electrola Radiola and kept the instrument playing continuously during the two days.” This was an RCA Victor combination radio and record-player, powered by electricity, and the records could be changed automatically. They sold two of these devices as a result, at a price of $1,550 each (by one method, that would be a $22,000 record player today). Later on, in 1948, they were advertising that they sold pianos, organs, radios, records, and televisions from their store location, now at 117 State Street. By then, Emerson Gray was the president, and Bradley Gray was the vice president.

At some point, Boardman and Gray moved its showroom up to 117 State Street. An article in 1950 identified them as the sole survivor of a once thriving industry. “During the [Second World] war, with the making of pianos in suspension, their Jay street factory was converted to the rebuilding of old instruments. Since the war, the company has been operating on a much-reduced scale of only a few custom-made pianos.” They remained on State Street until 1955, when they advertised their “new location” factory wareroom, the Jay Street facility. They remain in the city directory through 1960. In 1963, a Knickerbocker News photo noted the demolition of the Jay Street factory, with the cutline:

“MORE DEMOLITION – The saw-toothed hole in the side of the Boardman & Gray Building in Jay Street near Eagle Street testifies to the beginning of another demolition job in the South Mall. When the building is down, the back of St. Sophia’s Greek Orthodox Church, at left, will be visible. Built in 1891, the building once was used as a carriage and sleigh manufacturing plant.”

So, in all, Boardman and Gray was in business about 125 years. Despite a glorious history, and many of its instruments surviving to this day, when the end came it was barely noted. You can see a restored 1878 model being played here.

Interesting read.A search as to the significance of a “Boardman&Gray decal on an old Capehart console radio cabinet led to a search that brought me here.Stands to reason as I purchased it at an antique store in Preston Hollow,not far from Albany.