So, what befell the Albany Basin after the Dock Association dissolved in 1873? Business along the wharf continued, but declined. Its state as a nuisance was well documented in 1889. In 1892, both the Senate and the Assembly considered legislation to fill the Albany basin. “The upper portion of the basin had been abandoned, and in summer the stench which rose from it was almost unbearable. It had been commented on by people going north in the Delaware and Hudson trains . . . [The Albany] delegation had concurred concerning the advisability of closing the larger basin from the outlet of the upper basin to the Columbia street bridge, and straightening the inner line of the lower basin from Columbia street to Hudson avenue.” But there were still opponents, as the Chamber of Commerce was concerned that if the basin were closed, “there would be no harbor here and no boats would winter here, since they could not do so without damage. This was unfortunate at this time when a movement was on foot to deepen the Hudson river.” William Barnes, Jr., appointed by the Chamber to oppose the bill, proposed a commission to take another year to study the matter.

In addition, the boat operators believed the whole thing was a theft by the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. There was a proposed amendment to the constitution of the state that would donate, “absolutely free,” the Albany basin (containing an area of over 23 acres of state canal lands now walled up behind the constitution of the state) for a grand site for a union depot and freight terminus and for the sole use and benefit of the New York Central and Hudson River railroad, the West Shore railroad and the Delaware and Hudson canal railroad monopolies.”

Well, they weren’t wrong. Marcus T. Hun declared that the upper basin was useless to anybody and a source of malaria, and that leaving the lower part was fully adequate to meet the needs of the boats, and that the basin had not been filled with boats for years. He also said the station of the New York Central in Albany “was a disgrace to any city. He did not object to encouraging the roads to come here and build what they chose.” Mayor Daniel Manning was said to support the bill, but the city made no comments on what it wanted. Legislation wasn’t passed until 1895.

It didn’t happen right away though. In 1899, the basin was still a cesspool, and the “Central-Hudson” railroad was again working toward getting the rights to fill in the basin and to get an intercepting sewer built. Again, the plan was to built a sewer that would pass under land that would be created by filling in the basin “north of a point 100 feet south of Columbia street.”

Those who still held rights to wharfage on the western side of the basin were made responsible for dredging any parts that were not to be filled in . . . a strong incentive to agree to filling. “A line drawn southerly from the end of the pier of lock No. 1, along the present westerly boundary of the basin to the north line of Livingston avenue, and thence in a straight line to the intersection of the southerly line of Hudson avenue with the easterly line of Quay street, is established as the bulkhead line. No dock or pier shall be erected or filling in done easterly of said bulkhead line, except between the northeasterly line of Colonie street, southeast to the pier line hereinafter established, and a line drawn parallel to and one hundred feet distant southerly from the south line to Columbia street.”

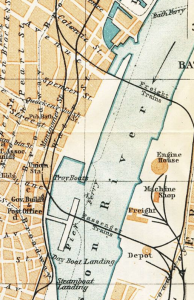

It’s not entirely clear when the actual filling took place, but a 1909 Baedeker map shows the northern portion of the basin filled in, while there was still a basin at the entrance to the canal.

It’s not entirely clear when the actual filling took place, but a 1909 Baedeker map shows the northern portion of the basin filled in, while there was still a basin at the entrance to the canal.

That still left the southern part of the basin. In 1906, another bill was passed and signed conveying the state’s title to land under water of the basin to the city of Albany. The city was then authorized to establish new bulkhead lines within the boundaries of the basin, and was allowed to grant to any owner of land or wharfage rights on the west side the “privilege” of filling in with solid filling that portion of the basin between the present bulkhead line and the new one and grant wharfage rights.

This being Albany, of course, any attempt at fixing a problem was bound to be seen as political opportunism. In 1911 the McCabe Commission, which we’ll have to do some studying up on, looked into Senate counsel James W. Osborne’s assertion that the filling of the basin was part of a long-term scheme to give land to the railroads, apparently discounting the issues of sewerage that were well-documented and the fact that the city didn’t own the basin until it was granted that title by the State as part of the whole deal that would fill the basin, build a sewer, and help build freight rail access.

A 1944 Times-Union article by Edgar S. Van Olinda looked back on waterfront improvements:

“In 1910, the Common Council, the D. and H. Railroad and the steamship lines began a waterfront improvement. The Albany Basin bridge was erected, new dock walls erected, the old buildings along what is now the Plaza [now the D&H Headquarters/SUNY Central Administration] torn down and work begun to make the site one of the most attractive in the city.

“The Albany Day Line ticket office, designed by the late Walter Van Guysling, was moved from Hamilton street to Division, in Broadway, and the land thereabouts made into a park, in which are many interesting markers, telling the stranger in Albany some of the history of the city in tabloid form.”

We’re still unclear, honestly, on when the remains of the basin were given over to the Albany Yacht Club, and other structures along the wharf were demolished. Still trying to sort that out.

1 thoughts on “The Fate of the Albany Basin”