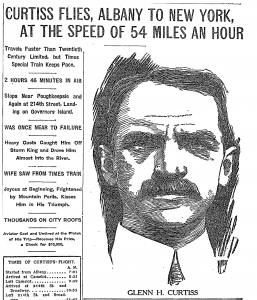

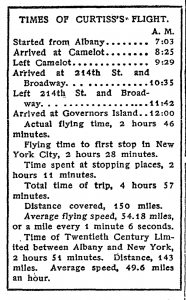

On May 29, 1910, the day finally came when Glenn Curtiss found the weather favorable, got into his aeroplane, took off from Van Rensselaer Island (now part of the Port of Albany) and flew on (with two stops) to Governors Island in New York City, meeting the challenge set by the New York World and receiving its $10,000 prize (something north of $230,000 in modern money). Although the prize was offered by the World, the New York Times covered and covered and covered the event, going so far as to engage a special New York Central train with priority rights to follow the plane down the Hudson, carrying reporters, photographers and Curtiss’s wife.

On May 29, 1910, the day finally came when Glenn Curtiss found the weather favorable, got into his aeroplane, took off from Van Rensselaer Island (now part of the Port of Albany) and flew on (with two stops) to Governors Island in New York City, meeting the challenge set by the New York World and receiving its $10,000 prize (something north of $230,000 in modern money). Although the prize was offered by the World, the New York Times covered and covered and covered the event, going so far as to engage a special New York Central train with priority rights to follow the plane down the Hudson, carrying reporters, photographers and Curtiss’s wife.

He placed a phone call to a newspaper office in New York City to check the weather there, and when assured there wasn’t “breeze enough to flap the flag against the Court House pole,” he replied, “That’s good enough. I’m Glenn Curtiss, and you can say that I have decided to make a start. I am going to leave Albany right away.” And so he did, garbed in canvas fishing waders (for warmth) , a leather jacket, and with cork life preservers strapped to his body.

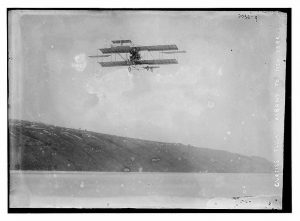

“Glenn H. Curtiss, until yesterday known as the aviator who had captured the international speed trophy at Rheims, arose from the tide flats of Van Rensselaer Island, at Albany, at 7:03 o’clock yesterday morning in the smallest biplane that has figured seriously in the world’s great flights. He sped upward to a height of 1,000 feet, maintained it for over forty miles, swung then over the Catskills at a far greater height, once attaining a maximum of almost 5,000 feet, dropped down above the Hudson waters for another forty miles, and landed finally at Governors island at noon. He had covered 150 miles in an actual flying time of 2 hours and 46 minutes, and had won for himself enduring fame, in addition to a prize of $10,000 offered for the feat by The New York World.

The flight, which sets a new mark in the conquest of the air, was made through a territory presenting a great variety of perils, far greater than any other stretch that aviators have tried. Side canons, high cliffs, eddying currents, and reverse currents shooting out of gulches into the Hudson Valley all played their part. One stretch made Curtiss fight every inch of his way, while his tiny craft tossed and pitched like a yacht in a hurricane. Through the difficult places, which include the treacherous Storm King pass, Curtiss pumped oil into his craft so plentifully that a long blue haze hung out behind him, fanning itself into shape behind, like a comet’s tail.”

A stop near Poughkeepsie was always planned, at the Gill farm in a place that was then called Camelot. The stop was supposed to take 15 minutes so he could refuel. Why there was no fuel when he got there seems to be a mystery. Curtiss brought the plane down at 8:25, “running twenty-five feet through the dewy grass before coming to a stop,” where about 20 people were waiting and cheered his arrival. He asked where the gasoline and oil he was expecting were, and Farmer Gill answered that he hadn’t seen it.

“Curtiss, who had been moving around looking over his machine, exclaimed: ‘Well, that’s too bad. I’m rather sorry I stopped. I could have gone on to West Point if I’d known that, or perhaps made New York.’”

Give the Times points for creative writing there. We’re going to assume that someone risking life and limb to make aviation history, doing something never done before, and chasing a $10,000 prize as well, probably said something stronger than “Well, that’s too bad.” His 15-minute stop turned into more than an hour, but more crowds were gathering and many of them came in automobiles. Curtiss asked the crowd if he could have some of their gasoline, which at least three of them were glad to give. His 50 horsepower V-8 engine had consumed all of five gallons getting from Albany to Poughkeepsie. After further inspections and minor adjustments to the aeroplane, he took off again at 9:25.

It was by no means an entirely smooth flight. The Times, watching from the accompanying special train, reported on the course:

“…Storm King, with all its terrors, was at hand. What the water navigators have said of it was none too strong to express the view of the aeronaut. The zigzagging motion of the earlier troubles now gave place to pitching and lurching, and made Mrs. Curtiss blanch with fear and hold tight to the window ledge from which she looked, while asking to know how quickly it would all be over. The castled parapets of West Point loomed across the river, fronting the higher backland hills. Curtiss seemed to like the going there, for he kept close to the trees and just sped along the top … Iona Island was immediately ahead and he was lurching, mostly in jerks straight up and down, worse than in any previous flurry. Every one on the train almost forgot to breathe, while Curtiss bobbed and jostled with the air to the island’s edge. There he seemed to be blown back by a head wind that held him in spite of his propeller’s thrust. His forward elevators suddenly bent down and the craft began to settle. His cause seemed lost and all thought he was surely going to land … Curtiss dropped maybe to within fifteen feet of the ground. Then he skimmed along, rose to avoid the roofs, passed just to the left of the powder plant tower and half way up its height, and was out into the broad bend at Peekskill.”

Apparently all that maneuvering took up more fuel than had been expected, because once past the Spuyten Duyvil, Curtiss set down again on the back lawn of the Isham mansion at Broadway and 214th street, where he was welcomed by one Minturn Post Collins, son-in-law of the late William B. Isham, who happened to be seated upon the veranda as the plane approached (as one so often is). The Times, whose reporters had to follow by automobile after the train veered off toward Grand Central Station at the Spuyten Duyvil, reported that Mr. Collins said “I am certainly delighted to be the first to congratulate you on arriving in the city limits, and I am glad you picked out our back yard as the place to land. You are great, there’s no doubt of that.” To which Curtiss was said to have replied, “Thank you, but what’s worrying me now is gasoline. Have you any that you can spare to replenish my tanks?” Collins did. A servant was dispatched. As one so often is.

Apparently all that maneuvering took up more fuel than had been expected, because once past the Spuyten Duyvil, Curtiss set down again on the back lawn of the Isham mansion at Broadway and 214th street, where he was welcomed by one Minturn Post Collins, son-in-law of the late William B. Isham, who happened to be seated upon the veranda as the plane approached (as one so often is). The Times, whose reporters had to follow by automobile after the train veered off toward Grand Central Station at the Spuyten Duyvil, reported that Mr. Collins said “I am certainly delighted to be the first to congratulate you on arriving in the city limits, and I am glad you picked out our back yard as the place to land. You are great, there’s no doubt of that.” To which Curtiss was said to have replied, “Thank you, but what’s worrying me now is gasoline. Have you any that you can spare to replenish my tanks?” Collins did. A servant was dispatched. As one so often is.

While waiting for the gasoline, “automobiles by the score came chugging up, the occupants, men, women and children, leaping out and running across the open field to get a chance to congratulate the aviator.” As a reminder of what era we’re talking about, the police department sent a horse-drawn patrol wagon up to the hilltop estate to help keep the crowd in check. It wasn’t entirely clear that Curtiss would proceed – he had reached NYC, after all, and could claim the prize, but he thought he could take off again from this location. The machine was refueled, and Curtiss enlisted the help of a few bystanders to give the machine a push, and he was off again. “All along Riverside Drive people had assembled to witness the flight, and in the upper parts of the drive small boys climbed trees. Warning of Curtiss’s approach was signaled by every vessel, yacht, launch, or steam barge over which he flew, and by the time the machine was off 150th Street the drive was crowded with admiring thousands, while from windows and roofs other thousands watched.” And so the scene continued, on down to the Battery, with onlookers leaning over the rails of ferries and steamships, gathering on the piers, watching the bulletins in Times Square. Today, you need to win a football game or have a sex tape to get this kind of public attention. Then, it was for a feat of daring science.

Curtiss landed safely at Governors Island, then still a military installation, greeted by officers and their wives. With a suspicious bit of poetry, one of the first officers to reach Curtiss was the Surgeon General of the Department of the East, Col. John Van Rensselaer Hoff. That his middle name was identical to the name of the island Curtiss had taken off from some hours before was not commented on, but neither could it have been missed. Col. Hoff was said to have panted hospitably (having run up to the plane), “We had almost given you up.” Curtiss responded, “I had to make two stops, one at Poughkeepsie and one at Inwood, you know.”

His wife arrived to greet him, and they kissed in front of the crowd. Curtiss removed his flying gear, including the canvas waders, full-length waders with boots built in.

“Dearie, I forgot my shoes, and left them up in Albany,” he said to his wife, and then a World representative arrived to announce that a check was being prepared in the office, and Mr. Curtiss had better come along to enjoy it.

From here on out, Hoxsie shall refer to him as Shoeless Glenn Curtiss.

1 thoughts on “When Glenn Curtiss Needs Gasoline, Servants are Dispatched”