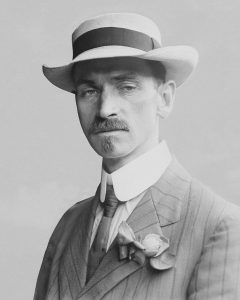

On May 26, 1910, inventor/aviator Glenn Curtiss was in Albany (we wrote about it here), alternating between his hotel room at the Ten Eyck and Van Rensselaer Island, where there was a two-poled tent that covered his flying machine, a cloth-winged biplane with a V-8 engine of 50 horsepower driving a wooden rear propeller. In case you wondered, he was paying the owner of Van Rensselaer Island for the privilege of taking off from his tilled field. The New York Times said the owner wanted $100 for the privilege, but eventually reduced his demand to $5. No doubt the exit fee might have irked Curtiss, but he was seeking a $10,000 prize offered by Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World newspaper for the first flight from Albany to New York City. The flight didn’t have to be non-stop – carrying that amount of fuel was considered impossible at the time – but only two stops for fuel were to be allowed.

On May 26, 1910, inventor/aviator Glenn Curtiss was in Albany (we wrote about it here), alternating between his hotel room at the Ten Eyck and Van Rensselaer Island, where there was a two-poled tent that covered his flying machine, a cloth-winged biplane with a V-8 engine of 50 horsepower driving a wooden rear propeller. In case you wondered, he was paying the owner of Van Rensselaer Island for the privilege of taking off from his tilled field. The New York Times said the owner wanted $100 for the privilege, but eventually reduced his demand to $5. No doubt the exit fee might have irked Curtiss, but he was seeking a $10,000 prize offered by Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World newspaper for the first flight from Albany to New York City. The flight didn’t have to be non-stop – carrying that amount of fuel was considered impossible at the time – but only two stops for fuel were to be allowed.

Not only was the length of the flight, nearly 150 miles, pretty much unprecedented, but no one had attempted such a distance over water, where those finicky and frail flying machines could be exposed to some very fickle winds that could cause disaster. While waiting for the right conditions, and for his aeroplane to be absolutely ready, Curtiss was paying careful attention to wind.

“When Curtiss arose at 4 o’clock this morning [May 26] a single look out of his hotel room window convinced him that an early morning flight was out of the question. The wind was blowing in gusts at the rate of from twelve to fifteen miles an hour, fishtailing from southwest to northwest. He went back to bed, did not get up again until 8 o’clock, and only after a leisurely breakfast crossed over to Van Rensselaer Island and the tent in which his fifty horse-power biplane was being assembled.”

Later he returned to the hotel, saying he wouldn’t attempt to fly unless the wind abated and changed direction. By 3 in the afternoon, the flight had to be deferred to the next day. The Times pointed out that the wind was actually worst at Albany and that further south on the route and all the way to Poughkeepsie atmospheric conditions were almost ideal and the course would have been safe.

The Times provided a very detailed description of the river topography, noting all the hills and valleys, places where the banks were close to the river and would demand Curtiss fly higher, and other spots where it widened out and he could stay close to the ground. Below Stuyvesant, “Safety demands, five miles further south, that the aviator who would continue to New York shall travel at least 500 feet high, for the steep, rocky banks of the river, it was evident, caused queer wind swirls and baffling air currents.”

Curtiss would be able to cut off some river miles crossing over some of the river’s bends. “The river shore is on the east bank a constant series of bays and indentations, and a great gain in the distance flown can be made by traveling on the hypotenuses of the triangles made by the sides of the bays.”

His plan was to refuel at the Gill farm, just short of three miles south of Poughkeepsie. But to get there, Curtiss would have to get some air, flying well clear of the railroad bridge whose top was 212 feet above the water. “A series of flags on both side of the river, starting about two miles north of the Gill farm, denotes the approach to the landing site, and there is hardly a likelihood of the aeroplanist running past the farm by mistake.” Once on his way again, he would have to deal with the extremely tricky winds of the lower Hudson valley and the Palisades, and once in the neighborhood of Fort Lee ferry (the George Washington Bridge wasn’t there yet), “Curtiss will have to pass over a constantly shifting panorama of moving vessels, whose smoke clouds and hot air exhausts will inevitably cause peculiar wind currents. This condition will require a cool head and a machine perfectly under control.” This wasn’t speculation – it was based on the experience of Wilbur Wright, who had flown from Governors Island to Grant’s Tomb in September 1909, and he found that passing steamships gave him one of the hardest tasks of his experience. He said in the future he would never attempt it at less than 3,600 or 4,000 feet in altitude.

On the 27th, the winds were no better, and the effort was delayed again. As evening fell, it seemed the wind had fallen as well, and Curtiss elected to take a trial run in the plane at about 7 o’clock. It was a fifteen minute flight that was nearly disastrous. He took off from Van Rensselaer Island, and had just gotten off the ground and over the tree tops

“when a sharp wind caught him abeam, whirled him around, and sent him zigzagging off toward the river, much as a kite dives when caught aloft in a sudden current of air. The aviator, however, seemed to recover his control after a long left drive at a sharp downward angle, and jumped rapidly upward on level planes. He was seemingly getting under way again in good form when another blast sent him whirling off to the right in among the tree tops, the planes [wings] tipping badly as the wind ripped through them. Curtiss rose to avoid the trees, and then something happened which was an entirely new experience for him. He said afterward he hardly knew how to account for it except on a theory that a wave of air bursting over him from the rear at a higher rate of speed than he was making carried him down as would a breaking billow of water an ocean bather.

What the hundred-odd watchers standing in front of the Curtiss tent, how half a mile in the rear of the flier, saw was the machine drop at terrific speed from a height of apparently about 200 feet right to the ground. Everyone held his breath, expecting that Curtiss had been seriously injured and his aeroplane demolished. Several women screamed, while a score of men set off across the intervening meadowland on the run. They were reassured, however, when they saw the Curtiss machine rise slightly and then settle down in good form.

The first to reach the spot found the aviator unharmed. He said that he had dropped through the air as if a vacuum had formed suddenly underneath him, and that the only reason he had not struck the ground before stemming his downward rush was that the planes when near the surface seemed to cushion upon the air and rebound slightly enough to send him gliding forward. . . .

When he wheeled the aircraft into his tent half an hour later Mr. Curtiss said that he would leave his hotel at 8 o’clock in the morning and would be prepared to fly before daylight in the morning mists. He added that his study of Catskill weather moods had convinced him that no time was so propitious for a flight as the hour just before the dawn, and he proposed to utilize that to its full advantage to-morrow.”

Tomorrow: The Successful Flight OR, When Glenn Curtiss Needs Gasoline, Servants Are Dispatched.