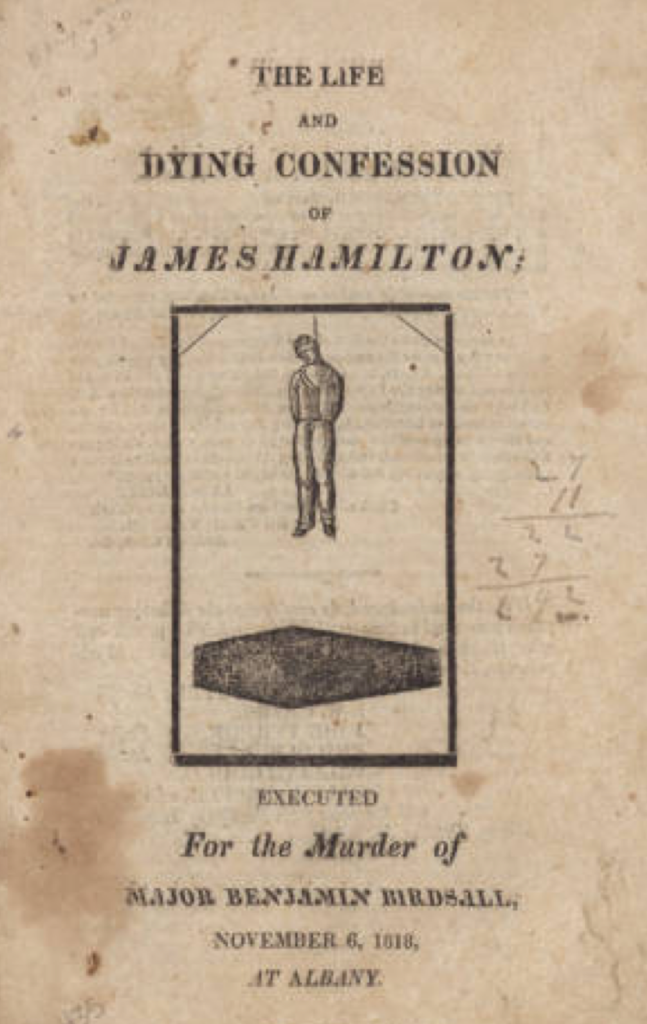

We mentioned yesterday that in the annals of early crime in Albany, one James Hamilton was hanged for the murder of Major Benjamin Birdsall. Before his hanging, Hamilton gave the account of his life to one Calvin Pepper, “who penned the same from the lips of Hamilton.” The Sheriff and Police Justices certified “that the following narrative was read to James Hamilton, while in prison and after sentence of death, and he declared the same, in our presence, to be true in all respects.” It’s a fascinating read. It begins:

“When a malefactor is about to expiate with his life, the offences he has committed against that society which has doomed him to an ignominious death, it is due to them and to himself . . . to give a brief history of his life, as well to evince his sincere penitence and contrition, as to furnish an awful lesson for those who are passing the giddy round of dissipation or are about to plunge into the dreadful abyss of wretchedness and sin . . .

“My birth, like my death, was the combined effect of infamy and sin. I was the illegitimate offspring of a mother whom I never knew, and of a father of whom I am equally ignorant, (the man to whom I once supposed I could give that appellation having disowned me) . . .

“At the age of ten years I was put, by my supposed father, to one William Cummings, who adopted me as his nephew, alledging [sic] he was my uncle. He sent me to the house of John Morrison, Esq. at Little Britain, where I attended the school of one Mr. Ellison, between two and three years, and made some proficiency in learning . . . from there I was sent to live with Barnabas Manney, in Blooming Grove, and attended the school of one Patrick Fellemyth, where I was whipped almost daily for fighting with, and abusing my school fellows. At this school I learnt nothing, paying no attention whatever to my book – Conceiving my master was too severe, I engaged ten other boys with myself to seize him one morning upon his coming into school, give him a beating, then throw him on the fire and keep him there until he was severely scorched. This project was luckily prevented by some young children . . . giving information to their father . . . and instead of our abusing the master, he, in presence of the parents, severely flogged us.”

He was shuttled about some more; how these families were found to take him in, he didn’t explain. In Orange County, he was to earn the trade of a tanner and shoe-maker, but one day he fought with an apprentice “and very severely cut him with my shoe knife.” He was “severely chastised with small rods,” and ran off. He ended up learning the trade of blacksmithing. Some time later he was in New York, where an acquaintance named Menton got him work on a small schooner. He fell to fighting with Menton, “and the captain coming on deck while I had Menton down, struck me, upon which I seized a billet of wood and instantly drove both Menton and my employer off the schooner.” He threatened them again, terrorized the ship’s owner into paying him (“threatened, upon his refusal, to pound him to a jelly”). More wandering and fighting, and “I then commenced visiting scenes of vice and prostitution.” Some might wonder what took him so long. Back in New York, he met a sailor named Hugh McClellan who helped him to live through gambling, and introduced him to “a decent house kept by the widow Pollis, who had one son and two daughters.”

One of those daughters was Catherine, about eighteen; he courted her for three months and married her, “but alas! Vice had at that time taken such deep root in my bosom, that I could not (although I dearly loved my wife) refrain from visiting prostitutes. I found at length, I was diseased by this course of dissipation, and daring not to visit my wife, I did (unknown to her) ship in a schooner, commanded by one Yates, bound to Norfolk, Va.” He bounced around the coast, coming back to New York, where he learned he was a father, “notwithstanding which, I made it a practice, at each port, to visit houses of debauchery.” He left and returned again: “by my wife’s request, I left the schooner and continued about two months doing no business, constantly gambling, drinking and visiting houses of ill fame.” A second child was born, which he did not believe was his. He moved back and forth between New York, Norfolk and Boston, where he appears to have become a pimp. “Here I became acquainted with a prostitute named Sally Smith; and she, together with one Charlotte Hatch, handsomely supported me, they often contending and fighting on my account.”

He took off with McClellan and ended up in Sand Lake working for Pliny Miller, chopping wood at seventy-five cents per cord. McClellan ran off with some borrowed money, another worker bit Hamilton’s finger, and “I continued with Miller about three months and worked very hard, but he being a tavern keeper, I fell in his debt for rum about thirty dollars.” Hamilton went to Albany, where he heard a soldier say “whoever enlists cannot be taken for debt and that clears them for ever.” He immediately enlisted, and found the life of a soldier pleasing. Not too surprisingly, he ended up in an altercation and threatened his sergeant, costing him a promotion to corporal. He was marched around the state in the War of 1812 and captured by the British, and was held prisoner 11 months. Released into Salem, Mass., he joined the navy, while still serving in the army. He was tried for desertion and sentenced to sixty days solitary confinement on bread and water, and six months hard labor with a ball chained to his leg. The tales of his escapes and recaptures, transfers, and reimprisonments become almost tedious. Apparently, desertion didn’t get you out of the service in those days.

Up in Sacketts Harbor, he became acquainted with a woman by the name of Caty Brown. “She used to wear black hair, neatly curled, and I thought her handsome – At length I went before a justice of the peace and married her [oddly, he had apparently taken the efforts to divorce his first wife]. About ten days after our marriage I found she wore false hair, her own being grey with age. Discovering the deception, I wished to part from her, and on enquiry found she had been three times married, and that her husbands were all living.” He didn’t stay with her.

There was more travel up and down the Hudson Valley, petty thievery, another wife, money hidden in a hat, arrests, escapes, more arrests.

Released from his last sentence on April 10, 1818, he went to Major Birdsall and offered to enlist. “By him I was sent to Greenbush, to be examined . . . I then informed the Major I had a wife, whom I wanted in the barracks . . . I then brought my wife from Moody’s stage house, where she was at work, to the rendezvous. The Major treated me exceedingly kind . . . .”

Another altercation with another soldier, and the Major ordered him whipped, but Hamilton said he bore him no ill will for this. However, there was another altercation, this time with a threat to shoot a black recruit:

“‘Now if you don’t clear out I will shoot you,’ and brought my piece to my face, cocked it, and if he had not removed I had intended to fire and wound him in the legs.” At that moment, the Major was drilling the evening parade. Hamilton announced to him, ‘Major, here I am,’ and the Major replied ‘Go to your ranks.’

“I stepped off two or three feet . . . towards him, and recollect of raising my gun, and hearing the report (the same having been cocked as before stated) and thus, awful to relate, I was the wicked instrument of sending an innocent, worthy, honored and lamented citizen and officer untimely to the grave, without provocation or excuse, except to gratify the sudden impulse of a most wicked, malignant and ungovernable temper, inflamed by intoxication. “

He closed his incredible narrative with this:

“Thus have I finished a narrative of my life – barren, I admit of any other scenes than those which are always connected with dissipation and vice. My life has been one continued and uninterrupted series of injustice towards man, and impiety towards God. Filled with passions of the most ungovernable kind, and with propensities which mark the ‘little villainies’ of the world, I had, on no occasion, cultivated a single sentiment of morality or religion. By gradations in vice, I at length arrived at the horrid crime of MURDER. No palliation to soften, no provocation to extenuate, no motive to excuse, can be urged for me in this last and barbarous transaction. My life has justly become forfeited to the offended justice of my country – My only refuge is my Saviour and my God. In the bloom of life I have become a victim for the tomb – No father’s tears to embalm my memory – No fond wife to assuage my woe, a deep and horrid gulph is now before me. Let the youth, then, beware how he indulges in the licentiousness and vices of the age – Let him remember his God in his early years, and that God will not forget him as he advances in life, and becomes an heir of immortality. – To the afflicted widow and children of Major Birdsall, what can I offer? In one moment I plunged them into unutterable agony and distress.”

Hamilton was hanged in Albany Nov. 6, 1818. The gallows was erected back of Elm Street and west of Eagle Street in that portion of the city known as Hamilton Hollow.